The veterinarian delivered the news at 12:18 p.m. I know the time because I texted my husband before she finished talking. The tests were normal, she told me, and it was likely a gastrointestinal issue. She didn’t promise Luna would be okay, but I held on to her words and felt my worry lift. I boiled chicken and rice to make up for her long day. She was disinterested in the food, but I chalked it up to the stomach bug. Hours later, we rushed back to the same vet hospital. This time, she was gone.

It happened quickly. Luna started to yelp loudly while lying on the floor of my room, and my gut told me she was dying. I frantically shielded my four-year-old from reality, rushing her to bed and telling her to not leave her room until morning. I wanted to scream at the woman who’d told me it probably wasn’t dire. The loss of my dog hit me like a train and still overwhelms me months later. I’ve written about my fear that my grief is too big, too dramatic — appropriate for a human, sure, but a pet?

In the time since, I’ve spoken to dozens of you about your experiences with pet loss and found comfort that I’m not the only one who’s been rocked by it. Luna’s ashes are somewhere in the house, but I can’t tell you where. I asked my husband to hide the urn, and I still don’t feel ready to look at it. I turn away when I see my neighbors walking their dogs.

Hardest, though, is the memory of the time when I thought my dog was fine. As I waited in the small examination room for the lab results to come back, I cradled her and tried to envision a universe where her symptoms were a false alarm. Imagine my delight when my positive thinking actually worked. I blasted Sabrina Carpenter’s album on the drive home and mentally planned out my outfit for the next day, not knowing how everything would end. Things were good until they weren’t. Isn’t that how it goes?

I could win a gold medal in a worst-case-scenario contest. I’ll check online highway patrol accident reports if someone doesn’t answer their phone. I peer at my baby monitor to make sure my kid is still breathing, pushing down the urge to check for myself in case the video feed is deceiving. My anxiety is no longer a novelty. It has become a companion.

I picture the worst because I don’t want to jinx myself. And in a twisted way, it makes sense. What are the odds that a mother worries about SIDS and her child dies of the condition that night? When I imagine bad outcomes, I’m protecting myself from any of it actually happening. I used to talk about this in therapy, but I gave up.

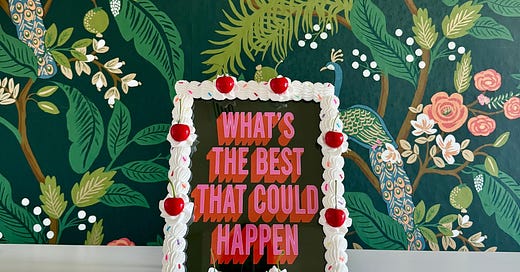

But four days after last year’s presidential election, I stopped my idle Etsy scrolling. The picture frame was dessert-themed and delightfully indulgent — fake icing with colorful sprinkles and cherries with their stems attached. I added it to my cart without a second thought, justifying the purchase because of the week we’d collectively had. I found a graphic with a sunny sentiment — What’s the best that could happen? — and printed it. The art became a source of joy.

For a few weeks, the picture did what it was supposed to do. When I sat down in front of my laptop to work on my book, I bullied myself into picturing an outcome that felt unrealistic. What if people ended up liking my work? Truly, someone relating to your words is one of the best things that can happen to a writer, but I sometimes feel afraid to even dream of it. At one point, I tried my best to imagine every single terrible thing someone could say in a 1-star review. It probably sounds like I crave reassurance, but honestly, it often makes it worse. So yes, framing a Pinterest graphic with a cheery saying may seem cheesy, but I had to do something.

Two days after Luna’s death, I returned to my office and almost threw it across the room when I spotted it. After a weekend from hell, of trying to stop sobbing while I explained the loss to my inquisitive, sensitive child, it felt like mockery. I still think back to that afternoon after the vet appointment and contemplate whether things would’ve been easier if I’d pictured myself losing her. The abruptness was the cruelest part.

To survive without losing your mind, you must choose to believe you won’t be the unlucky one. It’d be impossible to get in a car or send your kids to school otherwise. We all know the bad thing has to happen to someone, but we often embrace the probability that it won’t be us. I used to find comfort in statistics, too, until I lost a pregnancy when there was a near 99% chance I wouldn’t. Same with the postpartum psychosis I suffered five years ago — it occurs in 0.1% to 0.2% of births. And while a senior dog dying isn’t an oddity, the odds of it happening right after being told she wasn’t seriously ill felt low. Forgive me for the drama, but I have to ask if I’m prone to misfortune.

Still, I find pockets of hopefulness. With the exception of losing Luna four days into January, 2025 has been fine for me. Of course, the state of the world feels horrible, and I know that I’m very lucky to call it a good year. I’m also painfully aware of how quickly things can flip — my grandmother died suddenly last March, and it cast a shadow over the following nine months. When I wake up, I sometimes wonder if it’ll be the day I get a life-altering phone call. I’ve only lived it a couple of times, but I know it’ll happen again one day. No one lives forever.

A couple of months ago, I put the picture frame right-side-up on my desk. It didn’t feel like a big deal, but it signaled a shift for me, allowing space for a world where things might turn out all right. I’ve slowly let the positivity sneak back into my day, fighting the awful thoughts and envisioning a universe where everything turns out okay. And I’ve allowed that my doom and gloom doesn’t necessarily make the hard thing easier to process. Returning yet again to the afternoon before Luna’s passing, I’m torn between resenting the vet and wondering if the normalcy of it all was such a bad thing. Of course, if I’d known, I would’ve put my phone down, cried, and cuddled her nonstop, nudging forbidden treats her way. But having an ordinary last day wasn’t the worst thing. There’s no easy way.

As we all know, life blindsides in an instant, and optimism can make me feel silly when everything goes wrong. But my best-that-could-happen thought exercise allows me to trust, even for a second, that things will work out okay. And those moments of brightness do something for me, even if they feel borderline delusional. Of course, there’s a line between what I’m aiming for and a toxic positivity that prevents someone from actually coping and seeing the world for what it is. Terrible things are happening, and realism isn’t bad. I’m not saying we should plug our ears and sing la-la-la as the world burns. Still, my assuming every situation will end awfully hasn’t done much for me.

I’ve said I won’t get another dog because it’ll eventually die, and I can’t deal with it again. But I found myself scrolling the Humane Society’s website the other day, pausing when I spotted the saddest-looking Chihuahua I’ve ever seen. I’m not ready, not yet — but for a minute, I pictured the years of happiness Luna brought instead of the way it all ended. I still don’t know whether another pet is in the cards, but I’m feeling open to the idea. Even when a story is destined to have a sad ending, there’s beauty in the midst of it. Yes, I’d one day lose the dog, and it’d break my heart all over again, but wouldn’t there be plenty of “bests” between now and then?

Also on my mind…I’ve always said I only want two kids, and I mean it — I had a bilateral salpingectomy (fallopian tube removal) last year, so pregnancy isn’t happening for me. But I find myself struggling with the idea of my baby being my last. Sharing more thoughts below the paywall.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Ayana’s Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.